Why Provenance Is Failing Under Artificial Intelligence

As generative systems turn narrative coherence into a cheap resource, the art market confronts a deeper problem: documentation can no longer bear the evidentiary weight it was never designed to carry.

The current anxiety around AI and art fraud is often framed as a sudden escalation: better tools, faster forgeries, more convincing documents. That description is accurate, but it misidentifies the center of gravity. What is failing is not vigilance. It is provenance itself — or more precisely, the assumptions that once allowed documentation to function as evidence.

Generative AI has not introduced falsehood into the art market. It has automated something that was already there: the transformation of incomplete knowledge into authoritative narrative.

To understand why this matters, it is necessary to be precise about what these systems do — and what the art world has long asked documents to do on its behalf.

Coherence is Not Knowledge

Large language models do not retrieve facts. They generate plausible continuations. Given enough examples of catalog entries, valuation letters, and institutional prose, they learn how authenticity is spoken, not how it is established.

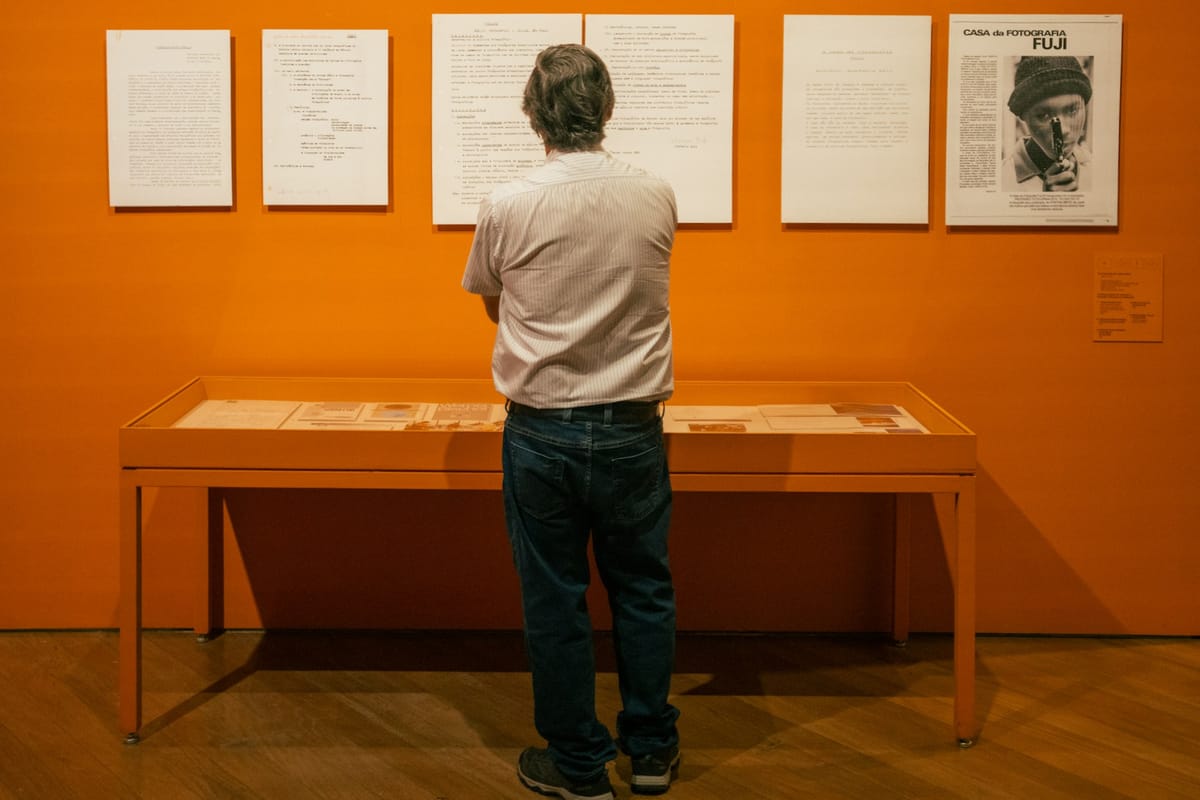

This distinction is not academic. Provenance is, by nature, narrative. It is assembled from fragments: partial archives, undocumented transfers, oral histories, lost invoices. For decades, professional judgment filled the gaps. Language signaled care, expertise, and effort. Completeness implied labor.

Generative systems reproduce this surface with ease. They do not “invent” in a random way. They resolve uncertainty into fluent form. Missing data becomes reasonable conjecture. Absence is converted into continuity.

This is why AI-generated provenance is so persuasive — and so dangerous. It does not look wrong. It looks finished.

Hallucination is Structural, Not Accidental

Much of the public discussion treats AI “hallucination” as malfunction. In reality, it is a design consequence. These systems are optimized to respond, not to withhold judgment. Silence is failure. Certainty is rewarded.

In the art market, that incentive structure collides directly with how trust historically operated. Gaps once triggered caution. Now they arrive pre-filled. The cost of doubt rises; the cost of acceptance falls.

This produces a new category of risk: documentation that is false without being fraudulent. Collectors and advisors increasingly rely on AI to summarize archives, reconstruct ownership chains, or contextualize works. When the output circulates — filed, forwarded, relied upon — speculation hardens into record.

Falsehood stabilizes not through intent, but through use.

Bias Follows the Archive

Another uncomfortable fact: AI does not hallucinate evenly.

Training data privileges what has been digitized, published, and canonized. Western modernism, blue-chip names, institutional collections — these dominate the record. Informal markets, regional histories, and artists outside dominant infrastructures appear as statistical noise.

When models “fill gaps,” they do so by leaning toward what is already overrepresented. This quietly reinforces existing power structures. Provenance for some artists becomes more legible, more complete, more “professional” — while others remain fragmentary or are overwritten entirely.

This is not ideological bias. It is archival bias, automated.

Why the Art Market Was Uniquely Exposed

Recent reporting, including coverage in the Financial Times, has framed AI primarily as an accelerant of art fraud. That diagnosis is correct but insufficient.

The deeper issue is that the art market long relied on documentation as a proxy for truth without requiring it to behave like evidence. Letterhead, tone, and institutional cadence carried weight because they were costly to produce. AI removes that cost.

When effort disappears as a visible signal, surface authority collapses. What remains is a system still behaving as if narrative coherence equals verification.

It no longer does.

As documentation loses evidentiary weight, risk does not disappear — it relocates, concentrating in underwriting decisions, acquisition committees, and private transactions least able to absorb uncertainty.

Not All AI is the Same

It is crucial to distinguish between generative systems and analytical ones. The former produce language. The latter measure patterns.

Machine-learning tools used in technical authentication — such as those developed by Art Recognition, advised by art historian Noah Charney — operate on a different epistemic basis. They analyze brushstrokes, compositional habits, and micro-patterns at scales inaccessible to the human eye. They do not invent narratives or complete histories. They test consistency.

These systems do not replace expertise; they constrain it. Their value lies precisely in what generative AI lacks: refusal to speculate beyond the data.

The current crisis is not “AI versus the art world.” It is the misuse of narrative-producing systems in evidentiary roles they were never designed to occupy.

Where This Leaves Provenance

Provenance is failing not because standards vanished, but because the conditions that once allowed documentation to carry weight have changed irreversibly. Language is no longer scarce. Institutional tone is no longer earned. Completeness is no longer evidence of work.

Authenticity is shifting away from narrative toward infrastructure: shared databases, forensic analysis, verifiable chains of custody. Large institutions will adapt. Smaller actors will bear disproportionate risk in the meantime.

This is not a moral crisis. It is an epistemic one.

The art market must decide whether it continues to reward documents that sound right, or whether it rebuilds trust around systems that can withstand synthetic fluency. Until that choice is made explicit, provenance will continue to fail — not at the margins, but exactly where decisions are made.

In a market where language is infinite, trust must become expensive again.

© ART Walkway 2025. All Rights Reserved.