Why Artists Once Slept Twice: Rediscovering the Lost Art of the Second Sleep

Artists, insomniacs, and dreamers may still carry the old second sleep rhythm in their bones.

The Night Used to Have a Creative Middle: The Second Sleep

We call it insomnia. Our ancestors called it life. Continuous sleep is a modern invention. Before electric light compressed the night into one seamless stretch, people everywhere—Europe, Africa, Asia—slept in two acts: a first sleep and a second sleep.

The interval between them was a pocket of consciousness so familiar that medieval letters, diaries, and even Homeric verses mention it casually. Families stirred fires, whispered prayers, or visited neighbors. Couples reached for each other. Monks copied manuscripts by candlelight.

That interval—often around midnight—was not “lost” time; it was noticed time. The body rested, woke, and rested again, tracing a natural ebb of awareness that modern life has overwritten.

Yet the pattern remains coded in us. Many of us still wake at 3 a.m. and wonder if something’s wrong. It isn’t. It’s memory—evolutionary and artistic—stirring.

The Forgotten Studio of the Night

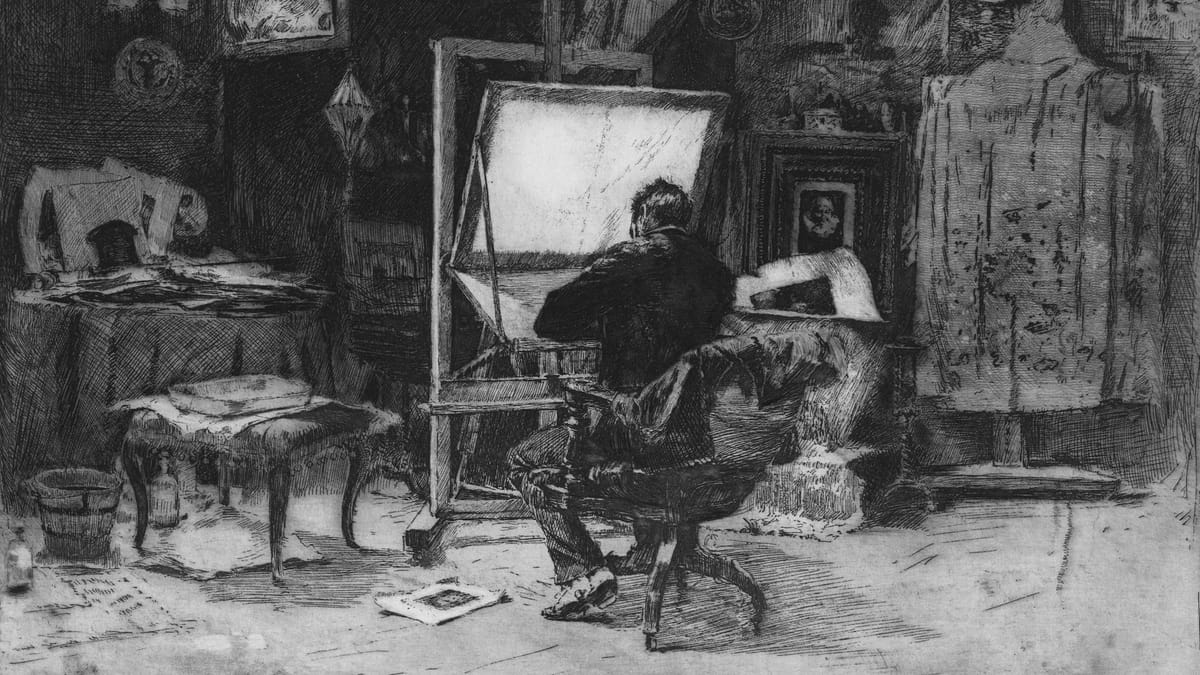

For centuries, this midnight wakefulness was a quiet workshop. People rose to write down their dreams, sketch symbols from them, or record the flicker between sleep and thought before it dissolved.

Dreams are fragile material. Those who kept dream journals knew that after the second sleep, the imagery fades like wet pigment drying too long. Renaissance artists and Romantic poets treated the midnight interval as a bridge: half of the mind still dreaming, half awake enough to catch the residue.

Because the second sleep consolidates new memories, it can overwrite fragile images from the first—another reason midnight note-taking mattered.

In today’s continuous-sleep culture, that bridge has collapsed. We chase productivity’s sunrise, not imagination’s darkness. The result is ironic—more rest, fewer remembered dreams. The creative psyche, once allowed to surface twice a night, now sinks uninterrupted and forgotten.

When the Night Lost Its Middle

Artificial light rewired the human clock. Gas lamps, then electricity, stretched evenings and pushed bedtime later. The Industrial Revolution turned circadian rhythm into factory rhythm—sleep became a single, efficient block.

By the early twentieth century, medical handbooks began describing “normal sleep” as continuous. What was once the standard human rhythm became pathology: insomnia.

Artists resisted instinctively. Vincent van Gogh painted The Night Café in feverish wakefulness, claiming it showed “the terrible passions of humanity.” Louise Bourgeois sculpted her insomnia into drawings. Even now, countless painters, writers, and composers describe the hour between sleeps as their most lucid.

Artists and the 3 A.M. Hour

What if the “witching hour” is actually a creative hour—a neurological twilight where imagination outpaces inhibition?

Neuroscientists note that when melatonin dips and cortisol rises near midnight, the mind enters a liminal alertness akin to meditation or flow. The analytical brain rests; associative thinking blooms.

Writers such as Haruki Murakami and David Lynch cultivate this state deliberately. Marina Abramović structures her endurance works to bend the perception of duration itself. Each, in a way, practices the ancient rhythm of segmented sleep—not to rest more, but to see differently.

“Wakefulness at night isn’t failure—it’s an ancient form of attention.”

Drawing From Dreams

In pre-industrial households, it was common to keep wax tablets or parchment by the bed. Leonardo da Vinci filled his notebooks with half-dreamed inventions and fragments of anatomical insight noted in the dark.

Today, we know that REM-phase images vanish within minutes unless anchored by movement or writing. The second sleep—by erasing the first’s residue—also erases its art.

Artists who rise briefly at night to sketch or jot a dream line reclaim that lost dialogue. The act is less about productivity than preserving the temperature of imagination before it cools.

Try it: wake naturally, write three lines, draw one shape, return to bed. The next day the symbols may look nonsensical—but together they map the night’s private exhibition.

Pro Tip: tag each note with three anchors—emotion, color, and verb (“fear / indigo / falling”). These survive morning better than plot details.

The Value of Delay

Modern creativity often worships momentum—finish fast, post faster. Yet art has always grown in delays: glaze layers that must dry, stories that need forgetting before rewriting, films that require distance to edit truthfully.

The second sleep is the oldest delay of all. It builds intermission into experience, a pause that lets perception reorganize. Psychologists call it “incubation”—the brain’s unconscious recombination of ideas while attention drifts.

The second sleep is delay made biological—a built-in intermission that lets ideas recombine before you touch the work again.

In the age of instant output, this pause feels radical. But slowness, as philosophers from Bergson to Byung-Chul Han note, is the texture of meaning. Delay isn’t a defect in creation; it’s the kiln that sets it.

Bezos’s One-Hour Rule and the Modern Morning

If the midnight interval honors reflection before daylight, Jeff Bezos’s “one-hour rule” revives its spirit for the modern morning.

Unlike other CEOs who sprint into the day, Bezos famously begins with what he calls puttering—coffee, reading, quiet breakfast. No screens for 60 minutes → calmer dopamine, clearer decisions, better recall. Neuroscience now supports him: research from the Stanford Lifestyle Medicine Program shows that avoiding screens for the first hour preserves gray-matter health, strengthens memory, and enhances decision-making.

“Passive screen time is like eating sugar but for your brain,” notes Stanford’s Maris Loeffler. The first waking hour, rich in natural cortisol and morning light, is when neural plasticity peaks. Creativity and learning are most flexible then.

Bezos’s slow ritual echoes the same wisdom the second sleep once enforced: let consciousness surface gradually. The human mind needs transitional space—between dreams and duties—to think originally.

Treat the first hour as a studio: reading, walking, thumbnail sketches—inputs before outputs.

Artists might call it dawn’s studio hour: time to read, walk, or draw before digital noise resets perception. Whether in the middle of the night or the first hour after waking, the rule is identical—protect the thresholds of awareness.

Light, Mood, and the Elasticity of Time

Studies from Darren Rhodes’s Environmental Temporal Cognition Lab confirm that low-light environments stretch perceived duration. Participants in dim or evening light judged two-minute clips as significantly longer than those in bright daylight.

Art has long exploited this elasticity. James Turrell’s installations trap viewers in slowed perception; Olafur Eliasson’s rooms of diffused light make minutes viscous. These works translate what segmented sleepers once lived nightly: time as a malleable, felt material.

As we note in Art Reflects Society, perception isn’t just a lens—it’s a material artists can mold.

When we flood our nights with LED glare and notifications, we lose that slow dilation—the sense that hours can expand like breath. Reclaiming darkness is not nostalgia; it’s neurological maintenance.

How to Reclaim the Second Sleep

You don’t have to move to a pre-electric village. Try restoring the night’s rhythm in small artistic ways:

- Dim the world after midnight. Use warm light; avoid screens.

- If you wake, don’t fight it. Rise briefly, stretch, read, or write in low light.

- Keep a dream sketchbook. Three words (emotion, color, verb) are enough.

- Hide the clock. Time anxiety kills both dreams and rest.

- Seek morning light. Step outside within an hour to realign circadian rhythm and mood—our go-to “creative ritual” for a clearer day.

The goal isn’t to fragment sleep but to restore dialogue—between rest and reflection, darkness and dawn.

The Art of the Interrupted Night

Every era hides its wisdom in what it discards. The second sleep, like analog film or oil glazes, looks obsolete until we remember what it enabled: nuance, patience, re-entry.

Artists today who feel guilty for waking at 3 a.m. might instead see it as inheritance. The body hasn’t forgotten. It’s simply waiting for you to pick up the pen it once held by candlelight.

The night used to hold two dreams—one for the body, one for the mind. Which one are you awake in?

Read Next on ART Walkway: