Ateneum's Gothic Modern Exhibition: From Darkness to Light

Gothic Modern at Ateneum, a groundbreaking exhibition that redefines modernism through medieval and Gothic influences.

Helsinki’s Ateneum Art Museum has seen many landmark exhibitions, but Gothic Modern: From Darkness to Light feels like an arrival. The culmination of a seven-year international research project, it gathers more than 200 works by artists from van Gogh to Kollwitz, setting them in dialogue with medieval and Northern Renaissance masters. This is not just another blockbuster—it’s a rethinking of modernism’s very foundations. And it begins with a quiet shock.

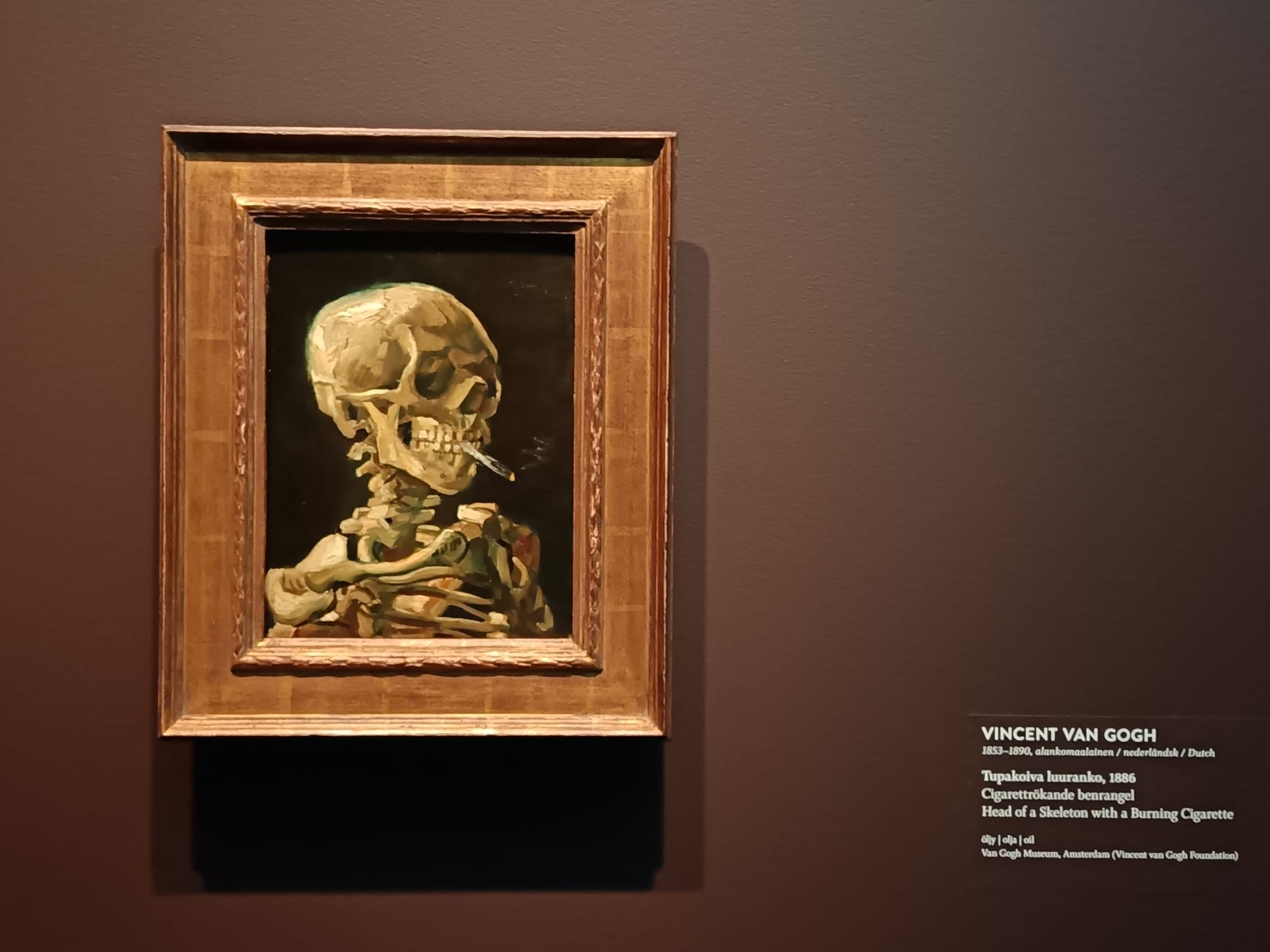

For me, that moment came almost immediately. I wasn’t prepared for it. Not fully. I had followed the press materials, skimmed the catalogue drafts, even corresponded briefly with one of the curators months before the opening. I knew Gothic Modern would be significant. What I didn’t expect was that it would leave me standing still in the middle of Ateneum, silent, stilled before van Gogh’s Smoking Skeleton. I was staring into an image that had been a joke in textbooks. Here, it was transformed into something ceremonial. Not ironic—but sacred.

This was not a blockbuster exhibition. There was no VR headset, no immersive tunnel, no AI chatbot to talk to van Gogh. There was just darkness. And light. And death. And it was exquisite.

“This wasn’t nostalgic. It was necessary.”

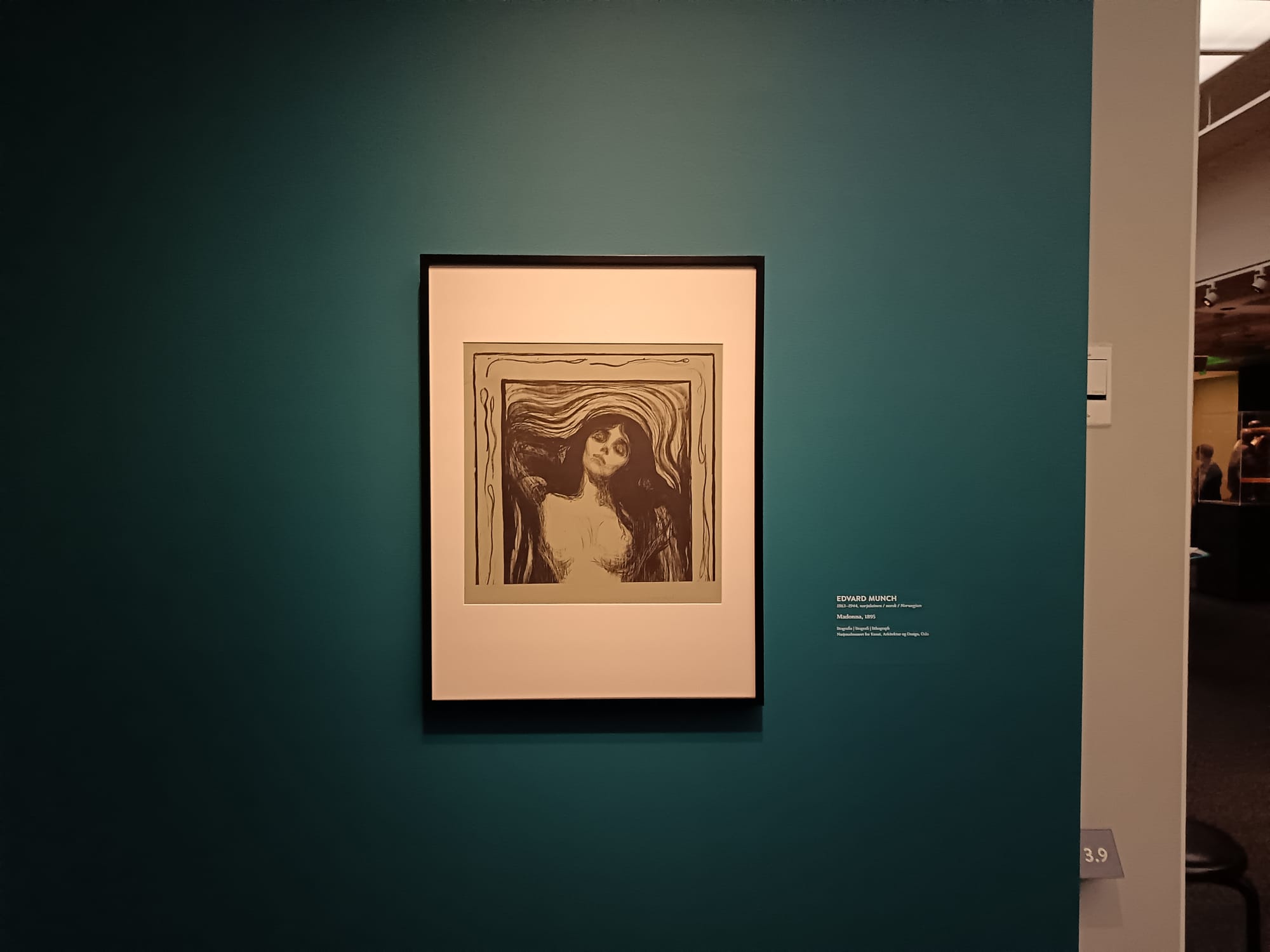

Gothic Modern: From Darkness to Light doesn’t simply revisit known works by Munch, Kollwitz, Simberg, or Schjerfbeck. It repositions them within a visual and emotional lineage that has long been ignored by mainstream art history. For decades, modernism has been cast as a rupture: away from religion, away from tradition, away from the body. This exhibition proposes a different story. It argues that artists around the turn of the 20th century didn’t just break with the past—they sought it out. Desperately.

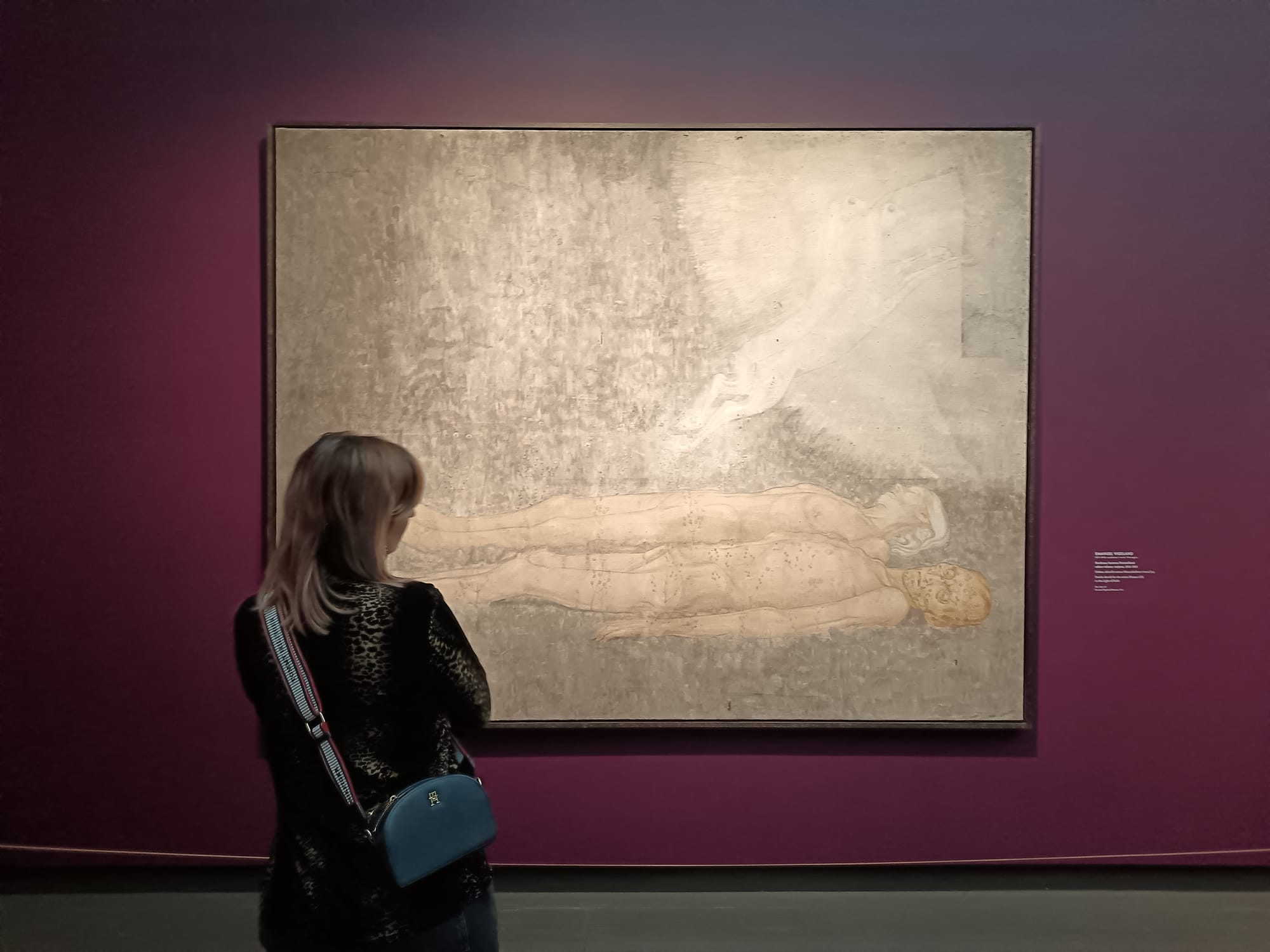

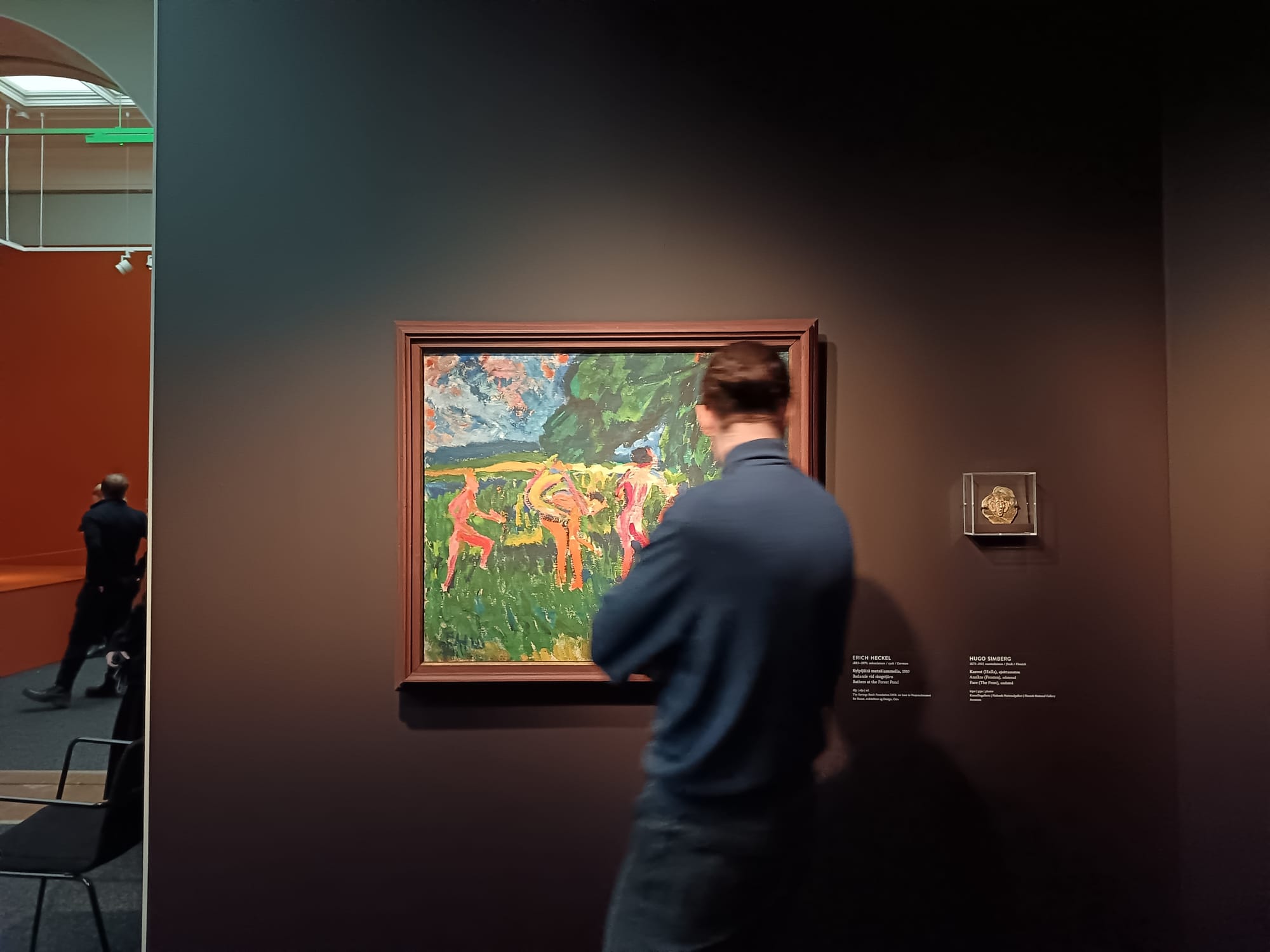

Professor Juliet Simpson — guest curator of Gothic Modern at Ateneum and lead author of its curatorial concept — notes in the exhibition’s gallery texts that artists at the turn of the 20th century “turned towards medieval and early German art to find ways of articulating their modern experience.” This idea doesn’t feel academic when you’re standing in front of Hugo Simberg’s Garden of Death or Kuolema kuuntelee (Death Listens), Joseph Alanen’s Tauti ja kuolema (Disease and Death), or Marianne Stokes’ Melisande.

“The Gothic is no longer a mood—it is a method.”

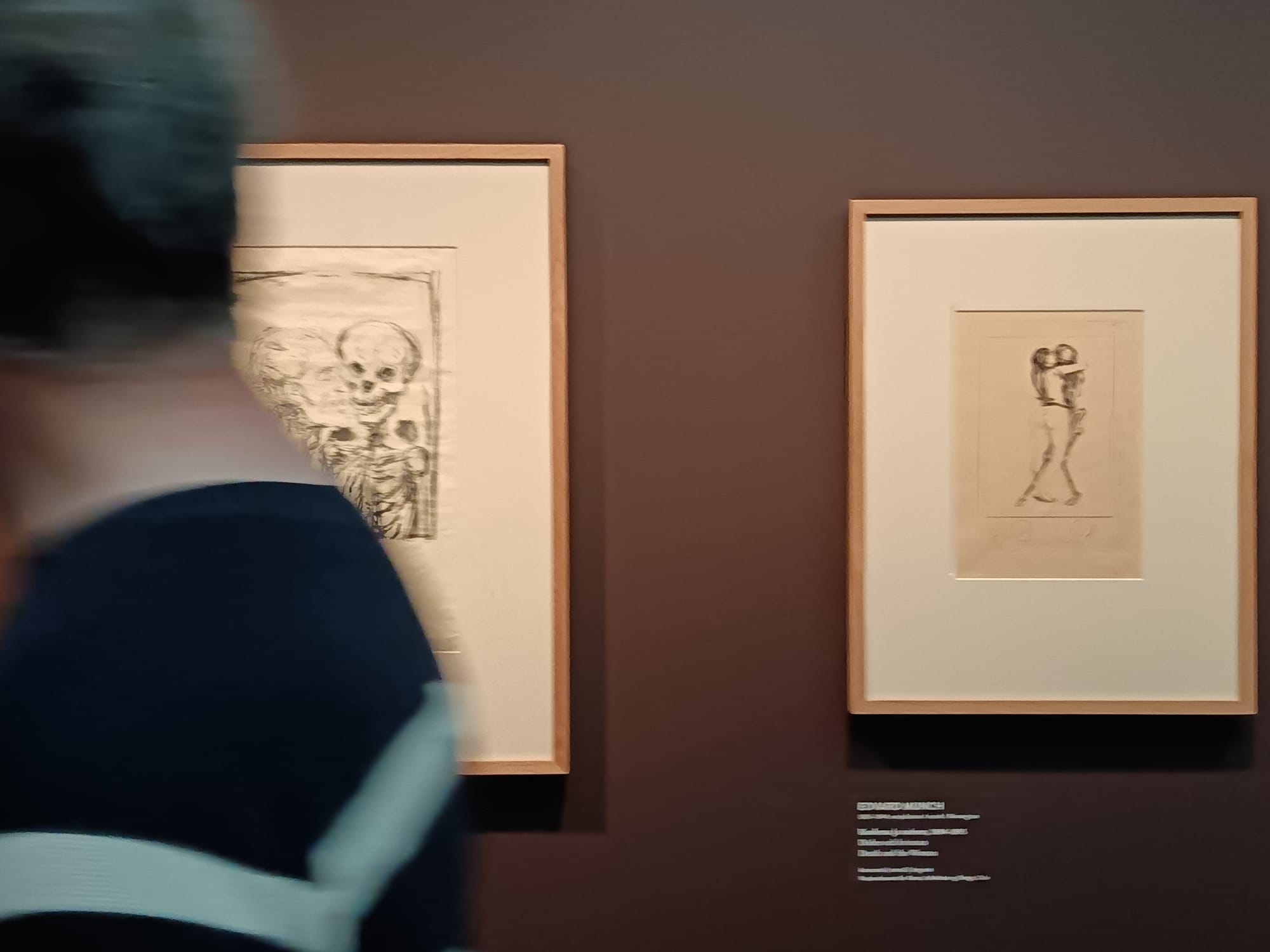

Over 200 works form a cross-European dialogue: van Gogh and Holbein; Munch and Dürer; Kollwitz and Cranach. These are not juxtapositions for effect. They are intellectual confrontations. They suggest a continuity of anguish, of erotic mysticism, of maternal grief and symbolic resurrection. What makes this show radical is not that it looks back, but that it reveals how modernism itself was haunted by the long shadow of premodern visual thought.

Highlights from Gothic Modern at Ateneum — Hugo Simberg’s “Kuolema kuuntelee” (Death Listens) and Joseph Alanen’s “Tauti ja kuolema” (Disease and Death) evoke the exhibition’s intimate confrontation with mortality. Photo by ART Walkway News

Emotion, Not Immersion

What astonished me most was the absence of spectacle. In an era where museums scramble to remain relevant through tech integrations and novelty tactics, Gothic Modern is a reminder of what happens when the work is allowed to speak. The show doesn’t ask the visitor to interact. It asks them to feel.

The lighting is spare and reverent. The atmosphere is close to devotional. A cathedral of mourning and reflection. If you listen closely, you can hear the floorboards creak under slow footsteps. People stay in front of Kollwitz’s Hunger for minutes without saying a word.

As Anna-Maria von Bonsdorff writes in Gothic Modern: From Edvard Munch to Käthe Kollwitz (2024), the project reveals “how the Gothic responds to periods of upheaval and reflects societal anxiety” — a vision that resonated so deeply it drew the youngest audience in Ateneum’s history. This is what Gothic Modern provides: a ritual, not a spectacle.

The Museum, Reaffirmed

Let’s be clear: this exhibition is a direct counterargument to those who say museums must digitize or die. With over 240,000 visitors, Gothic Modern became the most visited thematic show in Ateneum’s history. And it did so without gimmicks, trusting the intelligence of its audience—and the power of its material.

This is a moment for institutions to pause. The hunger isn’t just for content. It’s for depth. For discomfort. For transcendence. Gothic Modern proved that a well-researched, emotionally honest, and visually rigorous exhibition can reach further than a dozen social media campaigns.

“They came for the skulls, stayed for the sorrow.”

And more than that, it reached a new audience. Ateneum noted an unusual spike in younger visitors. Many were not museum regulars. They came for the skulls, stayed for the sorrow. That is not a gimmick. That is resonance.

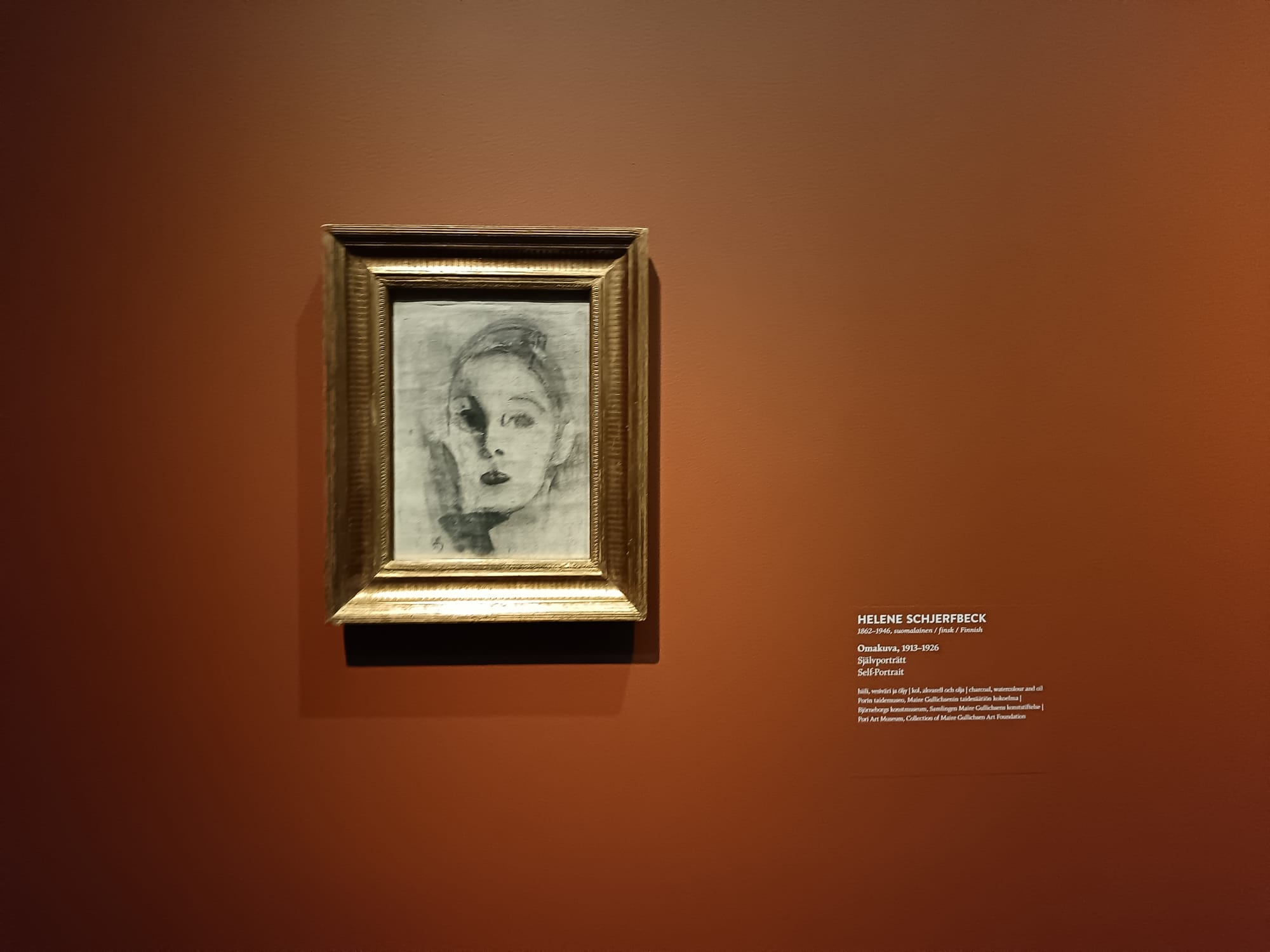

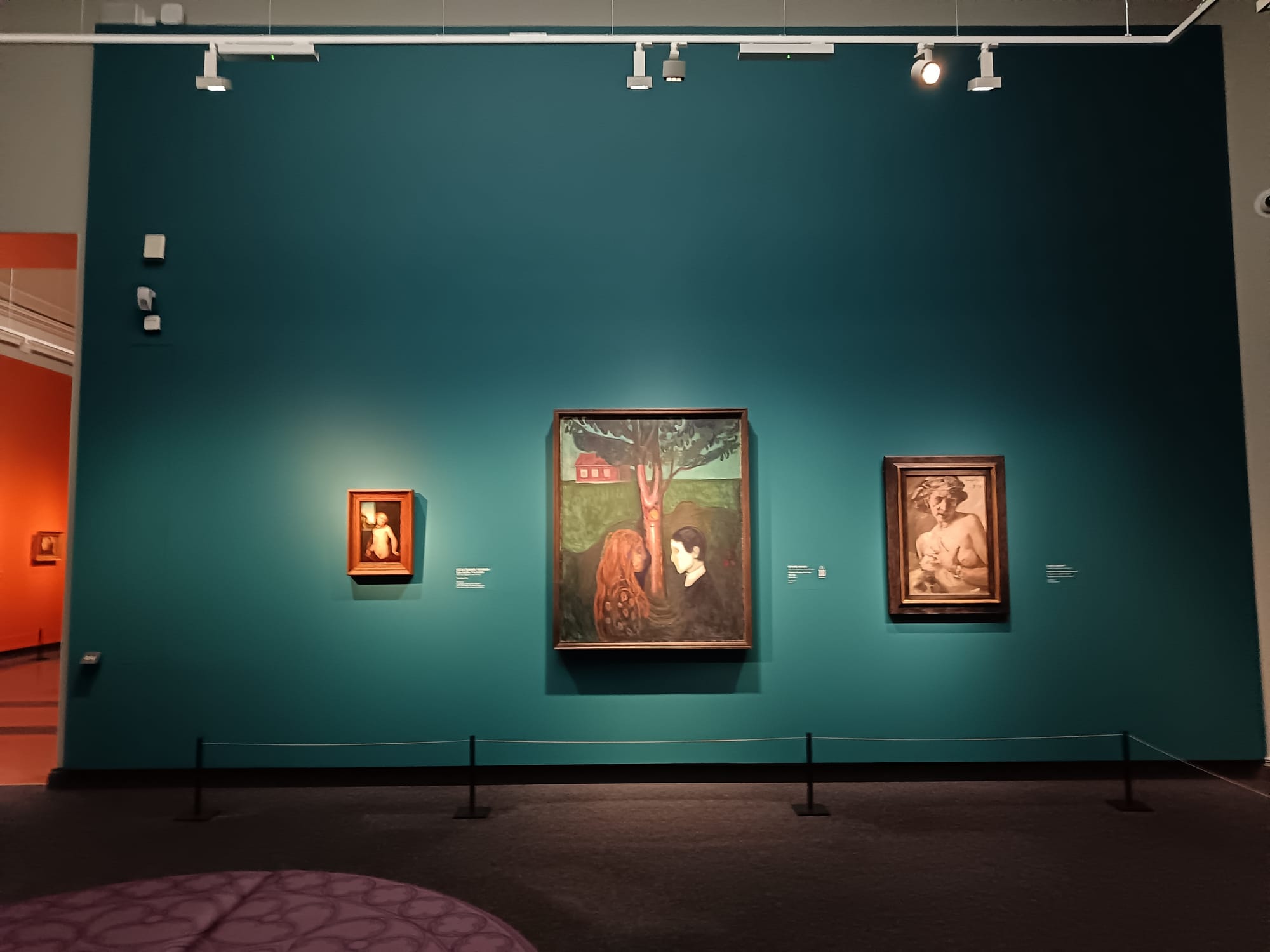

Contrasts in Gothic Modern at Ateneum — from the rust sun of Munch to the spectral portraits of Schjerfbeck. Photo by ART Walkway News

Afterlives of the Gothic

This show didn’t just present artworks. It reactivated them. Marianne Stokes, long relegated to Pre-Raphaelite footnotes, emerged as a painter of unsettling psychological grace. Schjerfbeck’s self-portraits, hung here like a sequence of apparitions, showed what happens when the body collapses into time. Kollwitz’s Mother with Dead Child looked like it could have been made yesterday. Perhaps it was. That’s what grief does to time.

“What grief does to time.”

Even the catalogue echoes this living quality. The essays are not mere accompaniments. They function as a second exhibition, tracing how cities like Berlin, Bruges, and Oslo became sites of emotional archaeology for modern artists. We learn how Simberg and Gallen-Kallela found spiritual kinship in medieval stained glass and church woodwork. How Böcklin, Munch, and van Gogh were not running from the sacred—but chasing it, trembling.

What Remains

I left the exhibition thinking not about death, but about belief.

“Not in a doctrine, but in the museum itself.”

Gothic Modern reminded me why art matters. Not because it innovates, but because it remembers. Because it hurts. Because it dares to speak when we cannot.

When I think of the images now—the rose-colored veil of Stokes’ Madonna, the rust-colored sun in Munch, the endless silence around Schjerfbeck’s face—I don’t see the past. I see us. Right now. Uncertain, aching, clinging to beauty like a dying language.

I didn’t want a screen. I didn’t want a QR code. I wanted to stay. Just a little longer.

Gothic Modern: From Darkness to Light travels next to the Nasjonalmuseet in Oslo and Albertina in Vienna. It is accompanied by a trilingual catalogue published by Thames & Hudson, Hirmer Verlag, and University of Chicago Press.

© ART Walkway 2025. All Rights Reserved.