The Tomb Trader: Edoardo Almagià and the Stolen Antiquities Scandal

If Almagià is the first name on your provenance, it is stolen,” declared Matthew Bogdanos of the Antiquities Trafficking Unit, signaling a decisive stance in the high-profile case against art dealer Edoardo Almagià.

In a story that spans decades and continents, Italian art dealer Edoardo Almagià finds himself at the heart of a sprawling investigation into the world of antiquities trafficking. This week, New York authorities issued an arrest warrant for Almagià, marking a dramatic turn in a saga that has tied the elusive dealer to a trail of centuries-old artifacts, all allegedly looted from Italy. According to sources, Almagià has been charged with conspiracy, the result of a labyrinthine investigation into the sale of cultural property that some claim belongs to Italy’s national heritage.

For Almagià, this is hardly the first encounter with suspicion. His name has appeared repeatedly in reports on looted Italian artifacts since as far back as 1992, when officials linked him to tombaroli, or "tomb robbers." Almagià has denied these connections, maintaining his innocence even as evidence against him has mounted over the years. The recent warrant, however, marks an escalation, signaling a determination by U.S. authorities to hold him accountable for transactions spanning decades and worth tens of millions.

The trail Almagià left behind is almost cinematic. According to the Antiquities Trafficking Unit, he meticulously recorded details of his business, preserving these records in a Renaissance-era chest beneath a marble statue. This small detail captures the enigma surrounding Almagià—a man who allegedly trafficked in antiquities but did so with a sense of grandeur, surrounded by relics of the very history he’s accused of exploiting.

Almagià’s dealings allegedly extended far beyond Roman sculptures and Etruscan pottery, touching some of the most prestigious institutions in the U.S. Among those institutions is Princeton University, Almagià’s alma mater, whose art museum owns several artifacts linked to him. Over the past eighteen months, Princeton’s museum has conducted its own internal investigations, releasing reports that detail the complex provenance of 16 artworks with connections to Almagià. This scrutiny has cast a shadow over the university’s collection and raised questions about how artifacts like these end up on display.

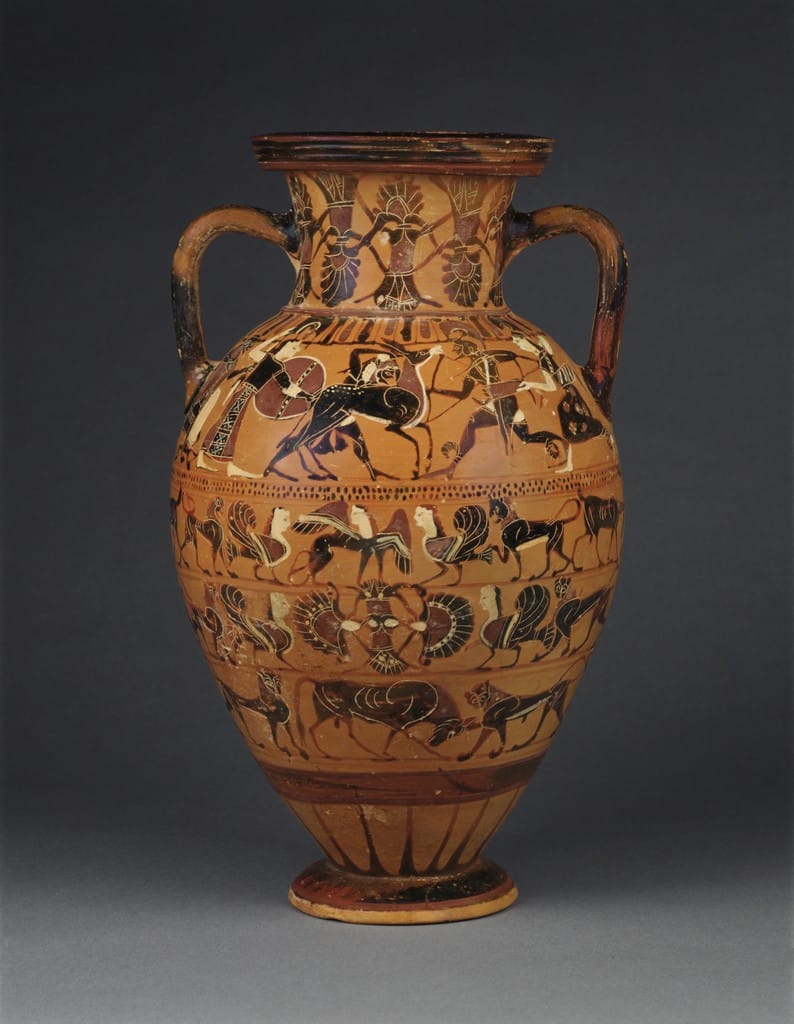

A selection of ancient artifacts from the Princeton University Art Museum, all acquired through dealer Edoardo Almagià: (1) Etruscan cinerary urn in the form of a house, 8th century B.C., hammered bronze, h. 29.5 cm, roof: 49.2 x 37 cm, walls: 39.7 x 30.6 cm (1999-70); (2) East Greek, Rhodian faience aryballos, early 6th century B.C., h. 6.1 cm, diam. 5.8 cm (2001-176); (3) Greek, Attic black-figure lekythos near the Painter of Athens 533, ca. 575 B.C., h. 18.2 cm, diam. 11.9 cm (y1990-10); (4) Greek, Attic Tyrrhenian amphora attributed to the Guglielmi Painter, ca. 560–550 B.C., h. 41.4 cm, diam. 24.3 cm (2001-218). All Photos: Princeton University Art Museum.

Almagià’s Case Illuminates the Battle Over Cultural Heritage and the Dark Market of Stolen Artifacts

In interviews, Almagià has downplayed these allegations, suggesting that much of his collection was legally obtained and dismissing the accusations as baseless. “They were never excavated illegally,” he claimed to the Princeton Alumni Weekly, “or they might have been excavated illegally, but that was before I bought them, and that no one will know.” His dismissal of the claims reflects his long-held stance, though law enforcement officials like Matthew Bogdanos, head of the Antiquities Trafficking Unit, are unswayed. Bogdanos has gone on record saying, “If Almagià is the first name on your provenance, it is stolen.”

Over the past decade, Bogdanos and his unit have pursued dealers like Almagià with a relentless drive. They’ve cast light on a dark, clandestine market where artifacts are bought, sold, and smuggled as easily as modern-day commodities. Almagià’s case represents a growing wave of international cooperation against trafficking, and his arrest warrant sends a clear message to the art world: the antiquities of Italy are not for sale, and those who attempt to sell them may find themselves facing the full force of the law.

The charges against Almagià add another chapter to the struggle between preservation and exploitation, legality and art. Whether or not Almagià faces a trial, his case highlights the perilous journey of cultural artifacts and the determination of modern institutions to return them to their rightful place.

ART Walkway News